Close

History of the Community

Of Thessaloniki

For more than twenty centuries, Thessaloniki was the refuge of the persecuted Jews of Europe. Historical centres of the diaspora, constantly moving in space and time, transplanted and took root in this city, creating a large Jewish Community, perhaps one of the most important in the world, especially during the period 1492-1943.

However, there is no clear evidence of the settlement of the first Jews in Thessaloniki, who are thought to have arrived around 140 BC, coming from Alexandria in Egypt. However, we do not have any testimony or evidence that would allow us to document this important event, which still remains an unsolved historical problem.Η αρχαία εκείνη εβραϊκή κοινότητα της Θεσσαλονίκης αποτελούσε τυπικό δείγμα ιουδαϊκής παροικίας σε μια μεσογειακή μεγαλούπολη των Ελληνιστικών και Ρωμαϊκών χρόνων.

Its members, the so-called “Romanians”, had adopted the Greek language while retaining several elements of Jewish or Aramaic origin, as well as the Hebrew script. It is this organized Jewish community of Thessaloniki in the early post-Christian years that the Apostle Paul will visit. And on his journey, we will also find the first written evidence of the Jewish presence in the city.

According to tradition, the oldest synagogue in Thessaloniki, where the Apostle Paul probably preached, was called “Etch Achaim” (Tree of Life). This synagogue, in the period of the Turkish occupation and until the fire of 1917, was located approximately at the junction of today’s Dimosthenous and Kalapothaki streets, i.e. near the harbour.

It is therefore known that during the Roman period the Jews of Thessaloniki experienced a regime of wide-ranging autonomy. Later, with the division of the Roman state into eastern and western, some Byzantine emperors dealt with the Jews by imposing special taxes or restrictive measures on their worship.

There were also some attempts at Christianization that did not yield great results, since they were condemned even by ecumenical councils, where it was often proclaimed that Jews were entitled to live freely and according to the dictates of their religion.

Middle Byzantine Thessalonica flourished despite the wars fought in its surroundings and the successive invasions of the Slavs and Bulgarians. Its population exceeded 100,000 in the mid-12th century. Around that time (1159), Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela set out from Saragossa in Spain on a long journey that would last more than thirteen years, arriving in Thessaloniki, from where he noted:

“After a two-day sea voyage we arrived in Thessaloniki, a large coastal city built by King Seleucus, one of Alexander’s four successors. Here live 500 Jews, headed by Rabbi Samuel and his sons, who are distinguished for their education. In addition to him, Rabbi Shabbatai, Elijah and Michael and other exiled Jews who are skilled craftsmen live there.”

In the years that followed, Thessalonike was tested by the siege and destruction by the Normans (1185), its occupation by the Franks in the Fourth Crusade (1204) and its reconquest, first by the Despotate of Epirus (1224) and then by the Empire of Nicaea (1246). This was followed by invasions by the Serbs, Bulgarians and Catalans, the Zealot rebellion (1342 – 1349) and the first Turkish conquest (1387).

In 1376, the first settlement in Thessaloniki of the Ashkenazim Jews, who came from Hungary and Germany in persecution, took place in the margins of these events. Ashkenazim arrivals would continue throughout the 15th century.

In 1394 a small group of Jews from Provence settled in Thessaloniki, while during the Venetian period (1423 – 1430), the settlement of Jews from Italy and Sicily expanded, and they founded new synagogues, forming, in turn, their own particular community.

The army of Sultan Murat II will appear in front of the gates on Sunday morning, 26 March 1430. And Thessaloniki will fall after a three-day siege. The entry of the Turks will be followed by a general looting, slaughter and captivity of its inhabitants. The Sultan will be forced to intervene personally, to put an end to the bloodshed and manpower drainage, will release several prisoners himself, at his own expense, and will arrange for the settlement and revitalization of Thessaloniki by transferring Turks from Yannitsa, but also Christians, to whom he will grant various privileges such as exemptions from certain taxes and communal self-government. All this, however, can be characterized as a prehistory of Thessaloniki Jewry.

The decisive event for the fate not only of the Jewish Community, but also of the entire city, is the settlement of 15 to 20,000 Spanish Jews from 1492, who, finding refuge in the Macedonian capital, will give it a new physiognomy.

The event that defined Spanish policy towards the Jews was the Reconquista, the war to reclaim Iberia from the Arabs, who had been established there since the early 8th century. The Reconquista ended on 2 January 1492, when the Arab State of Granada was finally abolished. And it is precisely then that the national, political and economic considerations that had imposed the hitherto tolerance towards minorities and the lack of any form of religious or racial intolerance are lifted, Ferdinand and Isabella, “the Spanish kings of the three religions”, as they wished to be called during the war, are now transformed into exclusively “Catholic kings”.

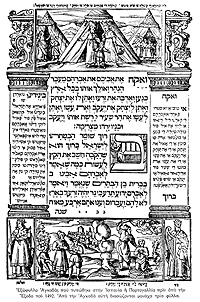

So we arrive at the fateful 1492. A royal decree of 13 March of that year requires all Jews to convert to Christianity or leave the country by the following August at the latest.

It is estimated that about 50,000 Jews were baptized superficially and remained in Spain. The rest, over 250,000, chose the path of exile. Some took the road northward, France, England, the Low Countries. Others chose Italy or North Africa. But most of them settled in the territories of the Ottoman Empire.

Sultan Bayezid II, motivated by the chief rabbi of Constantinople, Elijah Kapsalis, opened the gates of his territory to them and ordered the local governors to receive them cordially and facilitate their settlement.

“Thus the Spanish Jews, called Sephardim, will settle in all the major urban centers of the Ottoman Empire. Most of them, around 20,000, would prefer Thessaloniki, which had not yet taken over from the blow of its fall to the Turks. They were perhaps attracted by the city’s location in a key position. But perhaps the Sultans also sought to settle it with a new active population. With their arrival, the desolate state would awaken from its slumber and once again become a frontline economic centre, as it had been in Roman and Byzantine times. But the century following the exodus would also be the golden age of the spirit. Thessaloniki would become a great centre of theological studies, attracting students from all over the world, and producing outstanding personalities, rabbis, poets, doctors, whose fame would spread throughout Europe. Just then, in 1537, she would be honoured with the title of “Mother of Israel” by Samuel Uskwe, a Jewish poet from Ferrara.

The reputation of the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki will attract other persecuted Jews who will flee to it in search of a hospitable asylum. The first exiled Sephardim of 1492 would be followed by Jews from Sicily and Italy, who would arrive a year later, also persecuted by Ferdinand and Isabella. They would soon be imitated by King Emmanuel of Portugal, who on 5 December 1496 also ordered the Jews of his country to be Christianized or leave. The exodus of the Jews of Portugal began at the end of October 1497 and a large part of them fled to Thessaloniki. But even those who stayed behind, the superficially Christianized, the so-called Conversos or maranos, will be exiled between 1636 and 1560, victims of the ideology of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood).

In the 16th and early 17th centuries, new waves of refugees came from Provence, Poland, Italy, Hungary and North Africa. “Until the end of the 17th century it was rare for a ship to arrive at the port of Thessaloniki without leaving a few Jews behind,” writes P. Risal (I. Nehama).

Thus the Jewish element will prevail numerically as well. In 1519, according to Turkish archival sources, there were 1,374 Muslim families and 282 unmarried people living in Thessaloniki, a total of about 6,870 people. Christians numbered 1,078 families and there were 355 unmarried persons, totalling approximately 6,635 people. Jews number 3,143 families and 530 unmarried persons, for a total of about 15,715 persons.

The Jews would occupy the ruined and almost deserted districts under the Egnatia area of the city, from Vardari to today’s Diagonio.

From the beginning of the 16th century, Ottoman archival documents mention 16 Jewish quarters. There, in these districts, the Jews would cluster together, divided into autonomous, separate communities according to their place of origin, The focus of each community is the synagogue, which is in fact not only a spiritual and administrative centre, but also a tangible spirit of the separatist tendencies of each group of Jews, which tries stubbornly to maintain its independence from the others, The fluidity of the boundaries between the communities, however, and the business activities undertaken by some of them, from the early

But business activities also increasingly require a broader common approach, particularly as the communities deal with the Turkish authorities. And herein lies the seed of linking the independent synagogue-communities into a federation, loose at first and closer as time passes and circumstances dictate.

The offspring of this attitude is the common synagogue-school “Talmud Torah a gadol”, founded in 1520.

Texts of the 16th century inform us that craftsmanship was the main occupation of the majority of the Jewish population of Thessaloniki.The Jewish immigrants brought with them methods of work unknown until then. The most developed craft was the textile industry. Since 1515, the Ottoman government has met almost all of its needs for textiles with the products of the Jewish weavers of Thessaloniki.

He then agrees that the synagogues – congregations pay in kind the capital tax due to their members. The fabrics: these are used for the uniforms of the Turkish army, In 1540 the synagogues take over the production using their needy paid workers and allocating the profits for the maintenance of their charitable and educational institutions. A community mission to Constantinople in 1568, led by Moshe Almosnin, formalizes by a new sultanical decree the acquired privileges originally granted by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, whose documents had been lost in the fire of 1545. The Jewish Community of Thessaloniki is now recognized as a “Musselemlik”, i.e. an autonomous administrative unit directly subordinate to the High Gate. It can also procure raw materials at a price lower than that of the free market.

“Thus the Jewry of Thessaloniki would experience a long period of great prosperity which would be interrupted only at the beginning of the 17th century, with the discovery of new sea routes, the decline of Venice’s activity and the involvement of the Ottoman Empire in a series of lost wars. The political decline would come as a consequence of the economic one, as biblical studies declined significantly during this period, while mysticism and occultism flourished with the study of the Kavala and its main part, the Zohar. In the midst of this climate, in 1655, Sabetai Shevi from Smyrna appeared in Thessaloniki, proclaiming the expected Messiah, King of Israel and redeemer of the Jewish people. The resonance of his sermon will arouse the concerns of the Turkish authorities who will arrest and sentence him to death in 1666. It was then that Sabetai Sevi would convert to Mohammedanism to save his life. The Jews were already divided between those who believed him and those who viewed him as unhinged and an impostor. The former, some three hundred families, would follow him in his apostasy, creating the peculiar society of Jewish Muslims that came to be known as the “Donmeh” (apostate).

The mass defection created enormous problems. Hundreds of families, as well as the guilds, were divided. And this situation could not be dealt with either individually by the independent communities – synagogues, or by the federal bodies, despite the abilities and prestige of their leaders. Furthermore, the economic crisis will make it problematic to maintain separate, community-synagogue-based spiritual and charitable institutions. For this reason, these communities, which once stubbornly defended their independence, will successively cede more and more of their rights to the central federal authority, which, now having increased responsibilities and powers, will have to operate on a more systematic basis. Eventually, around 1680, the small independent communities would be consolidated into a single body, governed by a triumvirate of rabbis and a seven-member council of laymen.

We see, therefore, that even in these difficult years the Jews of Thessaloniki maintained their communal organization to an exemplary degree, despite the stagnation in the cultivation of letters and the circulation of ideas that came as a natural consequence of the schism, the economic crisis and the oppression of the gentiles.

The Jewish Community, however, will experience a real middle age during this period. But the renaissance would come towards the middle of the 19th century with the shift towards Western standards that went hand in hand with economic well-being, in the conditions of the awakening of the European Enlightenment, the industrial revolution and the neo-colonial exodus to the East. Within Judaism, new messages are taking shape in the movement of “Ashkalah”, i.e., the exodus from the intellectual confines of biblical and post-biblical tradition and the study and cultivation of contemporary extra-religious thought and art. Particularly in the East and in the city of Thessaloniki, some new socio-political conditions are taking shape as Ottoman despotism tries to change its face. The Genitsars were exterminated in 1826, while the Hati Humayun and Gulhade firmanas (1836 and 1854) granted some political rights to the non-Muslim nationalities of the empire for the first time. The wider penetration of Western industrial products would also transform Thessaloniki into an agency city and contribute to its expansion and modernization. Part of the Byzantine fortifications were demolished by 1869.

The fires of 1890, 1896, 1898 will offer the opportunity for an urban renewal. The burnt areas were rezoned, the narrow streets were widened, running water, electricity, trams and the railway that from 1871 would connect Thessaloniki with Constantinople and Europe. New projects are inaugurated in the port, modern banks are opened and in 1854 the first modern industrial unit is founded, the flour mill of the Italian-Jewish Allatini family, which is still in operation today. Jews also hold 38 of the city’s 54 major trading houses and make up the vast majority of the city’s workforce. Thessaloniki will of course retain its multi-ethnic structure, but the demographic and economic predominance of its Jewish community will be one of its most notable features. At the end of the 19th century, therefore, the Jews of Thessaloniki numbered over 70,000 souls, making up half of the city’s total population. Social welfare was expanding and was provided through modern charitable institutions, such as the Matanoth Laevionim, which maintained student soup kitchens, the Torah Umlacha, which provided financial support for needy students and ensured their professional rehabilitation, the Allatini and Aboav orphanages, the Lieto Noah asylum for the mentally ill, the Hirsch Hospital (now the Hippocratic Hospital), the Bikur Holim health institution and later the Saul Modiano nursing home. Education was further reformed with the modernization of the dozens of parochial schools and the traditional Talmud Torah school, and with the establishment, in 1873, of the Alliance Israellite Universelle school. Jewish children also make up the main square of the numerous foreign schools.

The Community will receive in 1891 thousands of refugees victims of the pogroms in Tsarist Russia and will house them together with the victims of the fire of 1890 (and later the fire of 1917) in the newly created settlements of Baron Hirsch, Kalamaria, 0151, Rezi Vardar, etc.

The first two settlements constitute the first attempt of organized building in Thessaloniki. El Lunar, the first newspaper to be published in Thessaloniki in 1864, was also Jewish. This was followed in 1875 by ‘La Epoca’ and later by the independent ‘La Impercial’, ‘Le Progress’, ‘Journal de Salonique’, ‘La Liberte’, ‘Opinion’, ‘L1 Indepentant’, the Zionist ‘La Nation’, ‘El Avenir’, ‘Renacencia Judia’, ‘La Esperanca’, ‘Pro Israel’, etc.

In 1908 the neo-Turkish comradeship consolidates its revolution in Thessaloniki and, based in this city, overthrows the Sultan Abdul Hamit. Immediately after the neo-Turkish revolution, the Zionist movement became openly active in Thessaloniki with the establishment of the ‘Bené Zion’ club and the ‘Makabi’ sports club. Zionism had first appeared in the city as early as 1899, initially under the cloak of associations such as ‘Kadima’, whose main aim was to disseminate the Hebrew language.

Almost at the same time, in 1909, the socialist workers’ federation, better known by its Spanish-Jewish title “Federacion”, was born from the numerous Jewish working class of Thessaloniki.It would operate autonomously until 1918, when, together with other Greek left-wing organisations, it co-founded the Socialist Workers’ Party of Greece, later renamed the Communist Party of Greece. The founder and leader of the Federacion was Abraham Benaroya.

On 26 October 1912 Thessaloniki is Greek again. The administration of the Community is immediately accepted by King George I who promises full equality of Jews within the framework of the laws. These promises are verified daily in practice. That is why the attempt of the Bulgarians to win over the Jews, since they lacked a serious ethnic base in the city, has no effect. On the contrary, the Greek administration is increasingly gaining the confidence of local and international Jewry, which is expressing itself more and more favorably to it and openly supporting Greek claims in the distribution of the European territories of the Ottoman Empire after the Balkan wars.

Thus begins for the Jews the new period of their integration into the Greek state. The first post-liberation decade, marked by national adventures, such as the Schism, the great fire of August 1917 and the Asia Minor Catastrophe, will close with the mass settlement of numerous refugees. The fire of 1917 in particular was a terrible blow. The community was unable to recover again, as 53,737 Jews were left homeless and the administrative buildings of the community and the chief rabbinate, thirty synagogues, the charitable institutions’ facilities, the Alliance’s teaching facilities and ten schools were destroyed. Thus many Jews would emigrate abroad during the interwar period and especially after the sad event of the burning of the Campbell settlement by extremist elements (1931). Most will settle in the Land of Israel. Nevertheless, the community will number over 50,000 souls in 1940. The Jews of Thessaloniki live in harmony with their Christian fellow citizens and perform their duty to the Greek homeland in full in the war of ’40-41′ as 12,898 of them will join the armed forces (343 officers). Their losses amounted to 513 dead and 3,743 wounded.

The enslavement of Greece to the Axis powers will mark the beginning of the end.

Sign in to your account